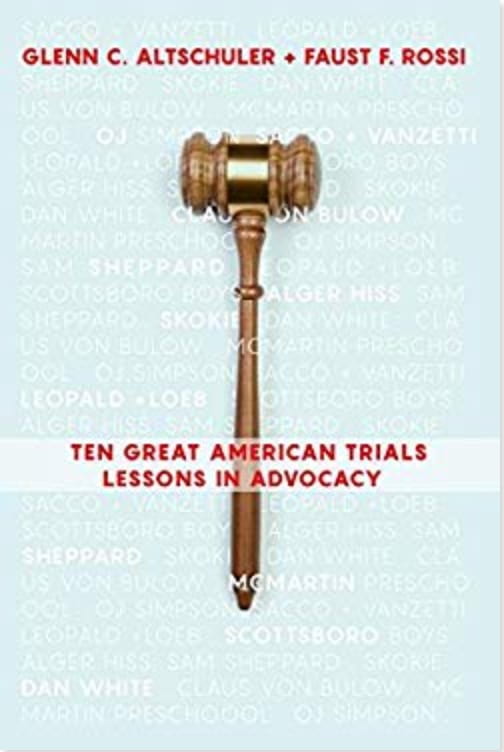

Ten Great American Trials: Lessons in Advocacy

By Glenn C. Altschuler and Faust F. Rossi

Date of Publication: 2016

383 pages

4.75/5☆

What Is This Book About?

In Ten Great American Trials: Lessons in Advocacy by Glenn C. Altshuler and Faust F. Rossi, the reader is walked through some of the best advocacy techniques in history while completely immersed in what the authors consider ten of the greatest trials throughout the 20th century.

The ten trials mentioned by the authors in this book are:

- The Case of Sacco and Vanzetti

- The Leopold and Loeb Trial

- The Scottsboro Trials

- United States v. Alger Hiss

- The Sam Sheppard Trial

- The Village of Skokie v. The National Socialist Party of America

- The Murder Trial of Dan White

- The Von Bȕlow Case

- The McMartin Preschool Child Sex Abuse Case

- People v. OJ Simpson

What Did I Like About the Book?

One thing I liked about this book was how it highlighted the responsibilities of government attorneys. Prosecutors and government attorneys are subject to additional rules outlined in the American Bar Association Model Rules. Their primary function is not to win their trial or case, but to ensure justice. In fact, Altschuler and Rossi actually quoted the ABA rules when they wrote, “ [t]he primary duty of a lawyer engaged in public prosecution is not to convict, but to see that justice is done.”[1] While some people may look at the role of a prosecutor as an admirable one, it is then the defense attorney’s job to put that admirability into question in an effort to defend their client. While discussing the case of Leopold and Loeb, who were both on trial for murdering an innocent boy in their neighborhood, the authors write about defense attorney, Clarence Darrow’s approach to the case by highlighting his closing argument. Darrow spent time during his closing talking about how “without considering the cause of a crime, one could not fairly decide on the punishment” and then talks about how lawyers, especially prosecutors, think of only punishment. Some food for thought: if a prosecutor’s job is to ensure justice, does that always require punishment? Should it? Could there be other avenues like pretrial intervention, pre indictment counseling, or drug court?

I really loved the discussion of United States v. Alger Hiss when the authors dive into the cross-examination of Dr. Binger. Dr. Binger testified on behalf of the defendant, Alger Hiss. who was a government official on trial because Whittaker Chambers accused him of being a spy for the Soviet Union in the 1930s. Dr. Binger testified that Chambers had a “psychopathic personality” disorder that made him more prone to lying. Thomas F. Murphy was the prosecutor in the case and he cross-examined Dr. Binger. The interesting thing about Dr. Binger’s testimony was that he never even examined Chambers. His entire opinion was based solely on watching Chambers testify in the previous trials, and then reading some of his writings and his German to English translations.

The cross-examination alone lasted five days, and I would have found the cross-examination very effective as a juror, but a part that Murphy picked up on during Dr. Binger’s direct-examination, which highlighted his active listening and ability to work on his feet, was Dr. Binger testified, Chambers rarely answered questions by stating facts. Dr. Binger said Chambers used the phrases, “it would have been” or “it might have been” way too often. Murphy brought up the 770 pages of testimony, and Chambers had only said those things ten times. And then, the most effective part, was Murphy pointed out that Dr. Binger had used either of those phrases 158 times. Right then and there, Murphy had basically killed almost all the credibility Dr. Binger had on the stand.

Another portion of this book I really enjoyed was during the discussion of People v. OJ Simpson. In People v. OJ Simpson, OJ Simpson was a famous professional football player, who was on trial for the murder of his ex-wife and another man, Ronald Goldman, who were found bludgeoned to death in her home. The authors mention that the government had a “mountain” of evidence against OJ Simpson, but the jury ultimately acquitted OJ Simpson. Something I have been thinking about since our last book, Inside Juror’s Minds: The Hierarchy of Decision-Making, was that it quite honestly doesn’t matter how much evidence you have, but how you present that evidence to the jury because they’re the ones who decide the case, and this was something really highlighted in this case. In People v. OJ Simpson, the prosecution presented their case very poorly. Through failed demonstrations (“If the glove doesn’t fit, you must acquit”), an abundance of unnecessary evidence, and choosing to put a damaging witness on the stand, the prosecution was arguably not building a case, but instead just passing the defense information for them to poke holes through.

Although the defense doesn’t even need to put on a formal case, the defense team of OJ Simpson moved through trial very strategically, playing to all the advantage they had, in order to defend OJ. For example, the defense certainly used OJ Simpson’s race, and used it to their advantage. In fact, when one of his attorney’s Robert Shapiro was in an interview with Barbara Walters, he said that the defense team of OJ Simpson, “not only played the race card” but that they “dealt it from the bottom of the deck.”[2] A time where this happened during trial, was when the jurors visited OJ’s home and his ex-wife’s home. When the jury arrived at OJ’s home, they were greeted by an entire redecoration job by the defense attorneys in order to emphasize OJ Simpson’s African-American identity. Another blunder by the prosecution in this case was that the Los Angeles Police Department and Nicole Brown-Simpson’s family had removed the personal effects in Nicole’s home, giving the home less emotion than that found in O.J.’s home.

What Didn’t I Like About the Book?

While I did love most of this book, something that I didn’t like was the chapter about The Village of Skokie v. The Nationalist Socialist Party of America. I think the authors describe why I didn’t like it pretty well, when they wrote:

Skokie lacks the element of mystery. There is unsolved crime, no charismatic lawyer, or naturally famous defendant, no authoritative United States Supreme Court decision, no jury trial, and no disputed facts.[3]

While I read a little about The Village of Skokie v. The Nationalist Socialist Party of America and it certainly seemed important, compared to all the other trials included in the book, it just wasn’t necessarily appealing or interesting to me. It lacked pizazz and felt almost misplaced alongside the other stories and trials which were all so entertaining.

What Did This Book Teach Me About Advocacy?

After reading and reviewing the third book for last month, Inside Juror’s Minds: The Hierarchy of Decision-Making, I may have had jury selection still stuck on my brain while reviewing our current book, and the important roles that jurors had throughout some of these “great” decisions, trials, and cases.

For example, the authors wrote that during the Sam Sheppard Trial, an “objective lawyer watching this case unfold would probably have concluded that although there was enough circumstantial evidence to convict, room remained for the jurors to have reasonable doubt.”[4] And through our reviews, we have learned that where we give jurors holes, we give them room for them to fill in their own pieces and bits of the story with their imagination, instead of facts they derive from the case.

The importance of jury selection is also continued throughout the murder trial of Dan White. In that case, Dan White resigned from his position as a member on the Board of Supervisors. Days later, when he attempted to get his job back, the mayor had chosen another candidate to fill the position. Dan White then went to City Hall and shot the mayor and another man who convinced the mayor not to reappoint him. This case was unique because it isn’t a whodunnit, we all knew who had committed the murders. The question left for the jury to decide was largely rooted in the why?

The prosecutor in this case was Thomas Norman, and Thomas Norman’s biggest mistake was failing to select a jury to find in his favor. The defense counsel for Dan White, Douglass Schmidt, had one goal in mind throughout this case – for the jury to feel sympathy for his client. During jury selection, Defense Counsel Schmidt used twenty-two challenges… Prosecutor Norman used four.

In any other case Thomas Norman would be trying, he would find jurors who represented, “law-and-order types, stable members of the community and conservative older men and women who might not shy away from the death penalty. Liberals were out, of course, given the perception that they tended to favor defendants.”[5]

But Thomas Norman wasn’t trying just ANY case here. The authors wrote, “Dan White was a conservative former police officer and fireman, a stable member of the community, and a traditionalist. In fact, Dan White, the accused, would normally be considered an ideal prosecution juror.”[6]

By being stuck in his ways, and not trying THIS case, but just trying A case, Thomas Norman helped the defense counselors pick a perfect jury for the defense. When the jury looked at Dan White, they related to him and saw themselves in him. In turn, the jury gave them exactly what Douglass Schmidt needed, sympathy to the defendant.

One of the greatest examples of the importance of jury selection is also displayed in the case People v. OJ Simpson. As discussed, race was a huge factor in that case. Ultimately a jury of eight African-American women, one African-American man, one Hispanic woman, and two white women reached a verdict. The authors wrote, “[a]dvocates must reach the hearts and minds of the jurors, and the very composition of this jury meant the defense task was half done before they’d even started.”[7] After the verdict was announced as the jurors walked out of the courtroom, the sole African-American male juror raised his fist towards the defense in a 1960s black power salute. There were lots of other attributes that drove that case to its conclusion, but jury selection was crucial.

How Am I Going to Be Able to Be a Better Advocate Because of This Book?

When learning the fundamentals of cross-examination, as young attorneys we are taught many things. Ask leading questions. Control your witness. But a commonly taught tip that not everyone always agrees on is: never ask a question you don’t know the answer to. In my opinion, that’s wrong. You can ask a question that you aren’t 100% sure what the witness will answer. But you need to be able to use that answer to destroy the witness’s credibility either way.

An example of this is during the Sam Sheppard trial. Dr. Sam Sheppard was a prominent doctor in Bay Village, an affluent suburb of Cleveland, Ohio, who was on trial for the murder of his wife Marilyn Sheppard when she was found bludgeoned to death in their shared home.

At the first trial, Coroner Gerber testified about the bloody imprint of a “surgical instrument” on the pillow next to Marilyn’s body, and as a surgeon, this was damaging to the defense’s case. During the second trial, Coroner Gerber made no mention of that instrument. F. Lee Bailey, Sam Sheppard’s defense attorney, brought this point up during the following cross-examination:

A: I am not sure.

Q: Would it perchance be an instrument that you yourself have handled?

A: I don’t know if I have handled one or not.

Q: Of course, you have been a surgeon, have you not, doctor?

A: No. Q: Do you have such an instrument back at your office?

A: No.

Q: Have you ever seen such an instrument in any hospital or medical supply catalog or anywhere else, Dr. Gerber?

A: No, not that I can remember.

Now here F. Lee Bailey has built a foundation, but these next couple questions are where that foundation becomes solid…

A: Oh, I have looked all over the United States.

Q: My goodness, then please, by all means tell us what you found.

A: I didn’t find one.

Q: Now Doctor, you know that Sam Sheppard was and is a surgeon, don’t you?

A: [Gerber nods to indicate yes].

Q: Now you didn’t describe this phantom impression as a surgical instrument just to hurt Sam Sheppard’s case, did you doctor? You wouldn’t do that, would you?

A: Oh no, oh, no.

Now, F. Lee Bailey has just destroyed all the credibility of Coroner Gerber. He didn’t say yes to that last question on the stand, but as a juror, wouldn’t you struggle to believe his “no”? This was a great example of asking open-ended questions that you may not know exactly how the witness is going to answer, but rolling with the witness and destroying their credibility either way.

[1] Glenn C. Altschuler & Faust F. Rossi, Ten Great American Trials: Lessons in Advocacy, 19 (2016).

[2] Id. at 378-79.

[3] Id. at 186.

[4] Id. at 168.

[5] Id. at 234.

[6] Id. at 235.

[7] Id. at 360.

[8] This was the second time this case had been on trial, so a lot of time, 12 years in fact, had passed between the actual crime and this cross-examination!

Seems like a great read for over winter break. Interesting cases, great work!

Your analysis made me want to read this book! Great job, Michaela!!

Definitely reading this over the break!